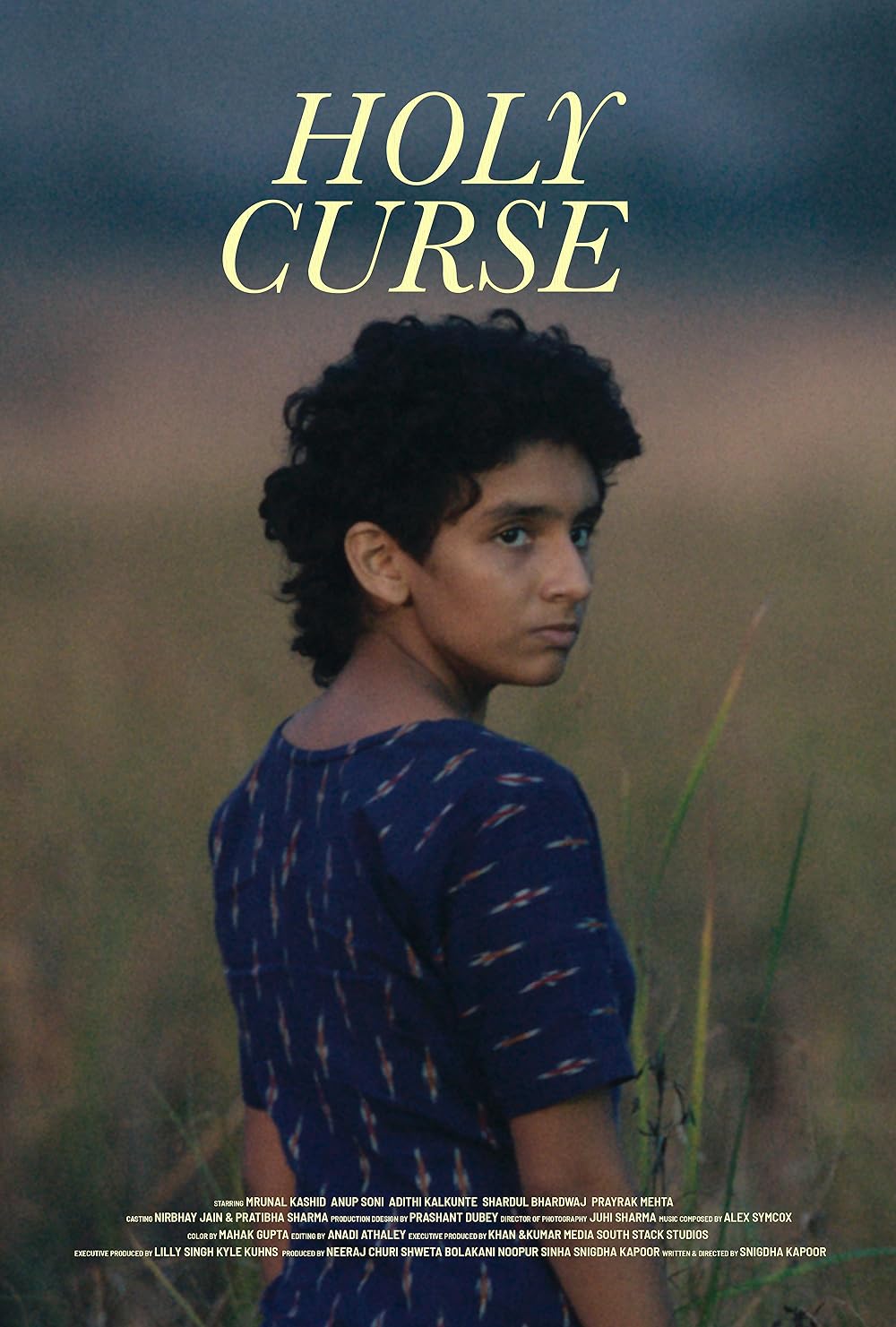

Set amongst the backdrop of a visit to India, Snigdha Kapoor’s Holy Curse is a journey unlike many others as it follows Radha, an eleven year old on a journey of the self as they battle against gender norms and their own path towards finding their identity. Surrounded by parents that mean well and show genuine love and care for their child while leaning on what they know in an attempt to help, the family, with the parents joined by Radha’s brother and uncle, set off on a journey to perform a spiritual ritual that would cleanse Radha of what they believe is a curse from a male ancestor, leaving Radha unable to live comfortably as the woman the family believes they are supposed to be, despite Radha’s protests.

Mrunal Kashid does a terrific job as Radha, showing the depth of emotions that comes with such an intense range of feelings. The angst, the confusion, the defiance and the sense of true self is so present in every scene, with Kashid doing such an excellent job in displaying those myriad emotions. Joining Kashid are Shardul Bharadwaj and Adithi Kalkunte as Ravi and Lata, Radha’s parents, as well as Prayak Mehta and Anup Soni as Radha’s brother Bittu and uncle, respectively. The entire family dynamic, as challenging as it is, is played so perfectly by the entire cast, each one with their own perspectives and thoughts on the way Radha is acting in response to being subjected to this unorthodox ritual in their own way, from the uncle’s frustrated insistence to Bittu’s brotherly teasing and eventual attempts at understanding, as well as Radha’s parents showing a love for their child even if they don’t fully know what’s going on with their child internally. Each performance adds another layer to the narrative, letting it feel real and lived-in as a story.

The film puts a spotlight on the ways in which children express themselves, and the response that adults around them give when they either don’t fully understand or use traditional societal norms as examples of what should and should not be. This creates the core conflict of the film it seems, as Radha’s journey to express themselves as they choose is pitted against what those around them believe they should be. The cast is excellent, and Snigdha Kapoor truly crafts a narrative that shows genuine care and respect for the topic this film tackles. It’s gotten plenty of attention, and rightfully so, and one can only hope its reach continues to grow, as Holy Curse is a can’t miss short film that should truly resonate with audiences, especially those who have gone through similar journeys to the one Radha experiences.

A big thanks to Snigdha and the entire cast and crew for creating such an incredible film! As a bonus, here’s a brief conversation with the filmmaker, who was kind enough to take the time to talk to us. For those of you who want to see the film for yourselves, The New Yorker has it posted on their official YouTube page in full.

What inspired the making of this film?

The film was inspired by moments I’ve witnessed growing up, where love and fear coexist very closely within families. I was drawn to the experience of a child who is trying to understand themselves, while the adults around them are also struggling, not out of malice, but out of uncertainty and social pressure.

What interested me wasn’t making a statement, but sitting with that discomfort. The parents in Holy Curse genuinely care for their child, yet they turn to systems they trust, hoping to help, without realizing the consequences. That dynamic felt deeply human to me, and it’s something I’ve seen across cultures and communities.

Making this film was a way to explore those quiet, painful spaces with empathy, without offering easy answers.

The film focuses heavily on gender norms, especially in children. What made you want to tackle this subject?

The film is really about a child who doesn’t neatly fit into the role they’ve been assigned, like being told “you are a girl and this is how you should behave.” I was drawn to that tension because it’s something many children experience in different ways, even outside of questions of gender identity.

The child in the film is nonbinary in the context of the story, but I intentionally didn’t label them beyond that because I don’t believe children experience themselves in fixed or fully formed terms yet.

What compelled me to tell this story was the gap between how freely children express themselves and how quickly society steps in to shape, define, and restrict that expression. Rather than offering conclusions about who this child will become, the film stays with them in the present moment, focusing on how their family and environment respond to difference, confusion, and vulnerability.

The journey of someone being able to come to terms with being non-binary is one that isn’t as often explored, especially when compared to gender transition, and as Radha is navigating it, it’s left rather vague. Was there any purpose to

this?

I wouldn’t frame the film as a story about transition from one gender to another. Radha isn’t moving from one fixed identity to another, and I was careful not to define their journey in those terms. What the film is interested in is how gender expectations are imposed on children, particularly when they’re read in a certain way by the world.

Radha is seen and treated as a girl by their family and community, and the conflict comes from the gap between that expectation and how Radha experiences themselves. The story is about what happens when a child doesn’t conform to the role they’ve been assigned, rather than about a transition narrative.

That experience isn’t limited to any one body or identity. I chose to stay with Radha in this specific moment because it reflects a kind of pressure that many children face when their expression doesn’t align with what’s expected of them. The film isn’t trying to explain who Radha will become, but to observe how they’re navigating the world as it is, right now.

What has this film (or any of your previous work) shown you about the differences between American and Indian cultures when it comes to gender identity and the act of transitioning?

I don’t think of this film, or my work more broadly, as a comparison between American and Indian cultures, or specifically about transitioning. What the film has shown me is how similar the underlying tensions are across places, even if the language or systems around them differ.

In both contexts, children who don’t conform to expected gender roles often encounter fear, confusion, and pressure long before they encounter understanding. The differences are less about values and more about how those pressures are expressed. In some spaces, there may be more visible language around identity, while in others the expectations are enforced more quietly through family, tradition, or social norms. What interested me wasn’t tracking a journey from one identity to another, but observing how families respond when a child doesn’t fit the mold they’ve been given. That dynamic exists in India, in the U.S., and elsewhere. Across cultures, adults are often acting out of care and fear at the same time, and children are left navigating that tension without the tools or power to define themselves.

If anything, making this film reinforced for me that these questions aren’t cultural outliers. They’re deeply human, and they show up wherever societies hold rigid ideas about who someone is supposed to be.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently developing my first feature, a coming-of-age story told through the perspective of two young girls. It continues my interest in intimate, character-driven storytelling and in exploring how young people experience the world around them.

I’m drawn to making films that start conversations and create space for reflection, because those are the kinds of stories I care about telling. I’m interested in work that encourages curiosity and empathy, and that invites people to think more deeply about the choices they make, rather than reacting from fear or assumption.

Thanks one more time to Snigdha for their time, and for sharing the film! Please check it out at the link mentioned above, you won’t regret it. Until next time!