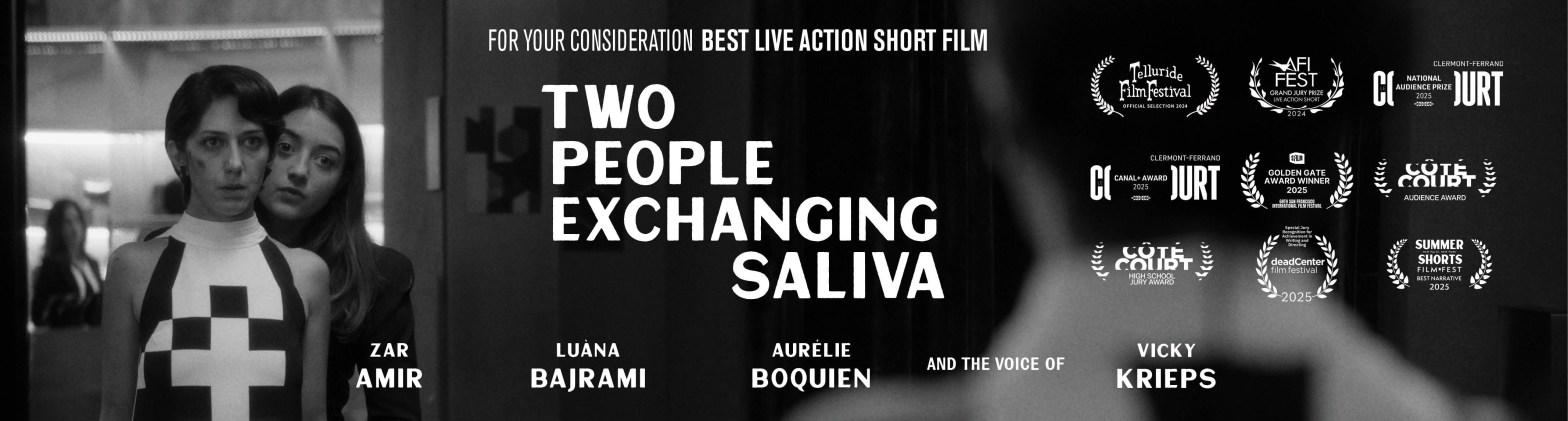

A beautiful, strange and emotionally powerful film, Two People Exchanging Saliva is a thirty-five minute black and white French opus about taboo, repression and forced restrictions on intimacy, living in a world where kissing is punishable by death and all currency has been replaced by getting slapped in the face in exchange for goods and services, with people who violate this law getting publicly and casually bound, put into boxes and thrown into a pit for daring to lock lips with another.

The film mostly follows the elegant but deeply unhappy Angine (Zar Amir), who frequents a high end clothing store. It’s there that she meets Malaise (Luàna Bajrami), a young woman who is just starting at the store and begins to develop a friendship with Angine. While their relationship grows and becomes more intimate, star saleswoman Petulante (Aurélie Boquien) begins to harbor jealousy towards Malaise for both stealing her best client and for garnering more attention, leading to the film’s ending conflict and consequence.

The film itself is a slow but intimate web of emotion and dynamics, with the older Angine and the bright and young Malaise finding a kinship in one another, despite the risk and despite Angine’s marriage to Chagrin (Nicholas Bouchaud), who seems to be someone who works in the production or design of these simplistic caskets for those who break the law. Watching the world exist, lived in and unafraid to show its darker edges is fascinating, the casual disregard for life when it’s living in conflict with the rules of the world bringing a dark contrast to the shining bloom of emotional growth between the two women. Filmmakers Natalie Musteata and Alexandre Singh, who wrote and directed the film together have built a reality that feels both strange and familiar, thanks to the development of the world and its allowances to feel lived in, despite its strangeness. The common sight of a bruised cheek from paying with getting slapped, the traumatic but seemingly frequent punishment for those who broke the restrictions on affection, it’s all there and like it’s the most normal thing in the world for those living in it, giving the film its own twisted realness despite the absurdity. Setting that upon a black and white film style just adds to the depth, to the idea that the world itself is black and white in terms of rules in a way that is heartbreaking and fascinating.

In addition, the cast is phenomenal, with the muted by emotionally vulnerable love story of Angine and Malaise captured beautifully by Amir and Bajrami and the immature jealousy of Petulante inhabited fully by Boquien being the main focus. It’s wonderfully acted, taken with all the seriousness the film needs to reinforce its concept and delivered on in myriad ways by the entire cast.

Overall, while it might sound silly to explain the rules of this film’s reality, the film is anything but funny, save for a few moments of absurdity when new concepts are revealed. At the core of the film is an emotionally powerful and devastating story of longing, repression, taboo and risk that is as beautiful as it is dangerous. A masterful job by Musteata, Singh and the rest of the cast and crew to bring this story to life.

To add even more insight into this incredible piece, we got the chance to talk to the writers/directors of Two People Exchanging Saliva, Natalie Musteata and Alexandre Singh! A big thank you to them for taking the time out to talk, please enjoy this short interview!

What was the inspiration behind the film?

Like so many of our ideas, this film was born out of bewilderment at the news. When we began writing in late 2022, Governor DeSantis’s “Don’t Say Gay” laws were being passed in Florida. In Iran, the death of Mahsa Amini had sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom protest movement. We often talk about the reductio ad absurdum of these stories—the way political realities, when pushed to their logical extremes, reveal something grotesque and surreal. That is often where our ideas begin. Surrealism, for us, is an artistic language that is deeply personal and subjective, yet also seeks to destabilize public and political spheres.

The particular shape of this film was also a response to a unique opportunity to shoot a small film set in a luxury department store. During the pandemic, Galeries Lafayette in Paris had begun a collaboration with the production company Misia Films called By Night, inviting visual artists, musicians, and performers to create works inside the store after hours, while it was closed to the public.

During our very first Zoom call with Misia, Alexandre had an instinctive idea: what if we told a story set in a society where people paid for things by being slapped in the face? It was an image that seemed to emerge fully formed, ripped from the unconscious. But the more we talked about it, the more we realized its resonance. The department store is such a loaded environment that speaks to thematics of power, wealth, social class and beauty.

And in a world where violence is normalized, it felt to Natalie that intimacy would disappear, which is how the second rule of this world came to be, namely, that kissing would be forbidden and punishable by death. As we mentioned, news stories—especially ones that we felt were absurd, almost otherworldly—played a big role in shaping this story. There was one in particular that we’ve spoken about before in which a young couple in Iran was sentenced to 10 years in prison for dancing in front of Tehran’s Freedom Tower. This sort of repression in the face of love and freedom, along with the rise of autocracies around the world, formed the bedrock of our absurdist tale.

The world of this piece is complex and very conservative in terms of affection. Was the world built around this sort of longing, or was the longing an effect of building a reality with these kinds of rules in place?

In this case, the rules of the world emerged first, and from those rules our characters: Malaise, Angine, and Petulante. We actually wrote several scripts set within this world, including one that explored its economy more directly, but ultimately we felt the story functioned best as a parable. What mattered most to us was not the mechanics of the world, but how these women move through it emotionally.

Angine is sophisticated and bourgeois, accustomed to an elegant, comfortable life she has never felt compelled to question. Her encounter with Malaise, a playful, free-spirited saleswoman who is open and true to herself, awakens desires Angine didn’t know she possessed. Petulante, by contrast, is a devotee to the world’s rules and hierarchies, clinging to them because she has nothing else.

From the outset, it was clear to us that this would be a story of repressed desire—one told through stolen glances and lingering touches. In this conservative world, where the method of payment is being slapped in the face, Malaise and Angine subvert that gesture, transforming it into something erotic.

Longing, then, is not the premise of the world, but its inevitable consequence.

The film is both very distant and very intimate at once. What kind of emotional effect were you trying to induce in the viewer by displaying relationships in this way?

The world of the film is lonely, distant, and cold, and it was important to us that the visual language reflected that emotional landscape. At the same time, the film is fundamentally a love story, so there are moments where intimacy felt essential—where the camera needed to be very close, and linger on the character’s faces, allowing the audience to experience their connection almost from the inside.

The film oscillates between these two modes, distance and closeness, and that tension mirrors our own creative approaches. Alex tends to gravitate toward wide frames, while for Natalie, cinema lives in the close-up. In that sense, the film is a dialogue between these two perspectives. We wanted the audience to feel both at once: the coldness of the world and, within it, the warmth and intimacy between two women as they begin to fall in love. Ultimately, the film is about the irrepressibility of love. We often say, “To tell someone not to love is like telling them not to breathe.”

Was there a reason to set the film in black and white as opposed to color? Was it to add another layer of emphasis to the nature in which people work in the world of the film, where things are very rigid?

The decision to shoot in black and white came very early in the process, for both artistic and practical reasons. Artistically, it allowed us to emphasize the geometry of the space and the almost authoritarian structure of the department store, which was originally built in the 1920s as a bank. Removing color reduces visual noise and distraction, and in a way functions like an X-ray, it reveals the bones of the building and lets us see the space as it truly is. Our background is in the visual arts— Alex is an artist and Natalie an art historian and curator—so we often think about composition in black and white. After all, a drawing begins with pencil on paper.

There were also practical considerations. Because the store is open seven days a week, we were shooting overnight, with limited access from around midnight to 6 a.m. Each morning, the displays had to be reset, which meant we had very little time to dramatically alter the space. Shooting in black and white became a way for us to put our own visual stamp on the location, allowing us to transform and slightly distance ourselves from reality while still remaining grounded in it.

What’s next for you?

We’re currently developing two feature films. The first is a longer version of Two People Exchanging Saliva, which we hope to shoot in early 2027. The second is a more ambitious work, also surreal, but this time exploring the absurdities of tribalism.

That’ll do it for this presentation from BitPix! Please be on the lookout for more as awards season comes ever closer, more films are put onto display, and we continue to off the best of the best in short films!